And why you should have 2 notebooks

Taking chemistry notes is more of an art than a science.

The irony in that statement is not lost on me, but there is no truly ‘correct’ way to take notes. Taking notes is inherently personal, and has to be curated to your individual style as a student. That said, there are a few techniques that experience and research leads me to recommend for taking notes in a fast paced environment like o-chem. While many of these tips are focused on synchronous lectures, they can also be applied just as easily to asynchronous lectures, though the ability to stop, pause, and rewind reduces the time pressure present of in-class lectures.

#1: Write them out

The research is very clear on this one, writing out your notes by hand is better than typing them1,2. The complex task of writing builds more neural pathways and leads to better recall than simply typing out the same information. For those with tablets or touch screen laptops, feel free to use a stylus to ‘handwrite’ hybrid notes if that is what you prefer. If lecture notes are provided beforehand, printing the notes and then writing onto them in class can also be effective. But you should definitely opt for a method that requires you to write, instead of type, your lecture notes.

#2: Don’t be neat

In addition to the increased recall when handwriting, most of your notes in organic chemistry should not simply be the words you are hearing in lecture. My notes in o-chem classes often included reaction schemes, stars, arrows, and circled parts indicating emphasis with small phrases like “BACKSIDE ATTACK” written all over the page. My class notes could sometimes end up using an entire page for a single example. While in class, focus on getting the information down onto the page as your own interpretation of what you are hearing. Synchronous lectures can be very fast paced, and being orderly and pretty is a great way to fall behind and miss large portions of critical information. Again, the goal is not simply to copy the exact words and schemes you are being given, but to put down the information in your own words and with your style of rough formatting. Doing this begins to form and reinforce those neural pathways that are critical to recall and application of the lecture material.

#3: Rewrite your notes

One of the best tips I was ever given for any class was to keep two notebooks. The first is the in-class notebook. Its purpose is outlined above; get the information down in time while building the start of the neural pathways. However, those notes are focused on speed, and therefore unordered and often difficult to parse quickly. This is where the second notebook comes in. After the lecture, ideally within a few hours, take your in class notes and rewrite them into a second notebook. In this notebook, focus on ordering your thoughts and notes. This is your opportunity to use other techniques such as color-coding that best fit your personal note taking style. The advantages of rewriting your notes is threefold. First, an ordered notebook is a much better reference when questions arise during practice and application (and you definitely should be doing practice problems.) Second, as with hand writing, the process of ordering and organizing your thoughts during careful rewriting also serves to reinforce neural pathways responsible for recall and application of information. Last, rewriting your notes helps to find any early holes in your notes and understanding. If you are going back in your notes and you can’t remember why a reaction proceeds in a certain way, or why a particular structure is favored over another, or any other of a million whys present in o-chem, this is your opportunity to pick it out and fix it early. Perhaps the most dangerous pitfall in o-chem is having a hole in your foundation of understanding, and spotting that hole as early on as possible gives you the best opportunity to patch it.

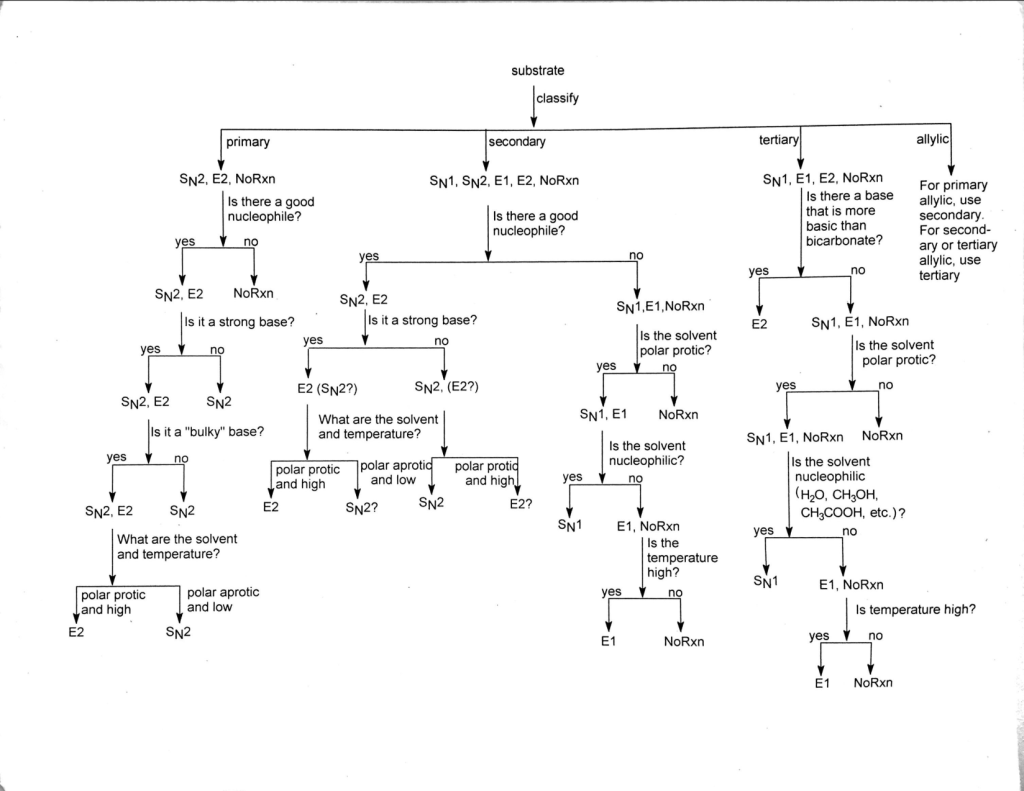

#4: When appropriate, completely reformat

While o-chem is far from pure memorization, there is undeniably a lot of things to learn. And often times, some of this information needs to simply be remembered before it can be applied. Flash cards are an excellent tool for this purpose, giving an easy, portable, and organized option. Repetition is the best tool for enforcing recall, and being able to whip out a bundle of flash cards and take 10-15 minutes between classes or just while waiting for friends to reinforce your memory is invaluable. For situations that require more information and detail, I often found myself turning to creating reference tables or schemes. Having a detailed and highly organized reference written in your own personal style helps massively during the most difficult varieties of practice questions like complex mechanisms and multi-step synthesis. These are far from the only types of reformatting you can do; let yourself be the guide for how you can best use your information.

This is far from a comprehensive list of how to take effective notes; it’s closer to my personal experience as a student now teacher of organic chemistry. While writing two separate sets of notes was what worked best for me, and it is what I recommend to all my students, it may not be what is best for you. Writing lecture notes is a personal process, and even if your style is incomprehensible to others, as long as you can read them, then they are effective notes. Find what works best for you, and let your notes be a reflection of yourself just as clearly as a mirror.

- Smoker, T. J.; Murphy, C. E.; Rockwell, A. K. Comparing Memory for Handwriting versus Typing. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2009, 53 (22). 1744–1747. https://doi.org/10.1177/154193120905302218.

- Flanigan, A. E.; Wheeler, J.; Tiphaine Colliot; Lu, J.; Kiewra, K. A. Typed versus Handwritten Lecture Notes and College Student Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review 2024, 36 (3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09914-w.